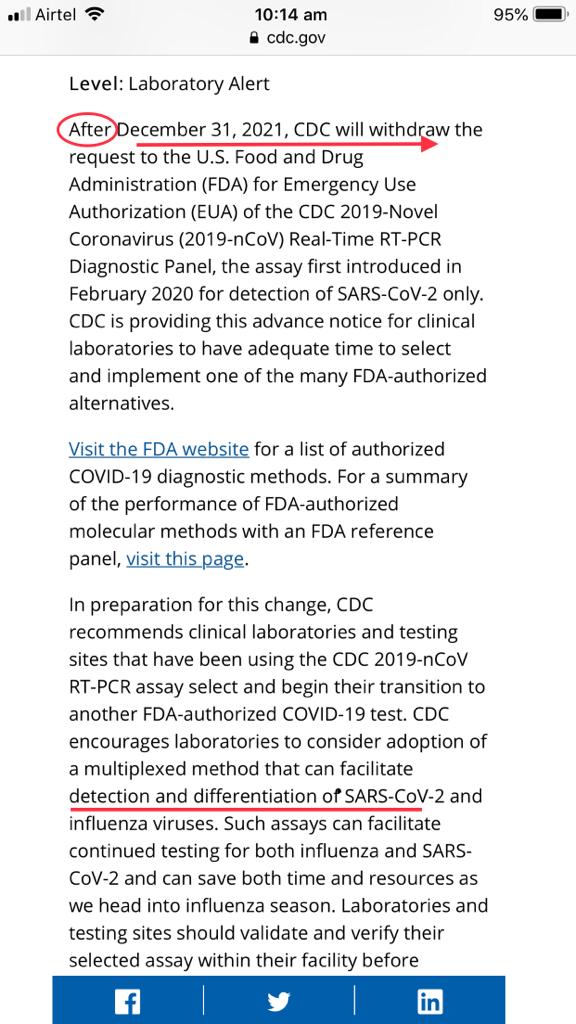

The CDC report highlights that the test used for detecting the coronavirus was flawed from the beginning. Even Karry Mullis, the inventor of the RT-PCR test, stated that it was not designed to test for the virus but was intended for lab use only. Despite this knowledge, officials chose to release the test for widespread use, leading to misinformation and inaccuracies in diagnosing COVID-19 cases.

CDC Report: Officials Knew Coronavirus Test Was Flawed But Released It Anyway -NPR

On Feb. 6, 2020, a scientist in a small infectious disease lab on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention campus in Atlanta was putting a coronavirus test kit through its final paces. The lab designed and built the diagnostic test in record time, and the little vials that contained the necessary reagents to identify the virus were boxed up and ready to go. But NPR has learned the results of that final quality control test suggested something troubling — it said the kit could fail 33% of the time.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via AP

Under normal circumstances, that kind of result would stop a test in its tracks, half a dozen public and private lab officials told NPR. But an internal CDC review obtained by NPR confirms that lab officials decided to release the kit anyway. The revelation comes from a CDC internal review, known as a “root-cause analysis,” which the agency conducted to understand why an early coronavirus test didn’t work properly and wound up costing scientists precious weeks in the early days of a pandemic.

In addition to learning of the early warning, reviewers determined the Respiratory Viruses Diagnostic Laboratory, run by a highly regarded scientist named Stephen Lindstrom, was beset with problems, including “process failures, a lack of appropriate recognized laboratory quality standards, and organizational problems related to the support and management of a laboratory supporting an outbreak response,” the review said.

The CDC declined to make Lindstrom or anyone else available for an interview and declined to discuss the unreleased internal review. A spokesman would only say that the agency had “acknowledged and corrected mistakes along the way.”

Like building a house without a hammer

In late January, the tally of confirmed COVID-19 cases seemed relatively manageable — about 4,500 confirmed cases worldwide and under a dozen confirmed in the continental United States. In a pandemic, public health officials say, the best hope to keep the numbers low is to determine who else might have the virus and where it was spreading and then concentrate efforts on those areas first.

The CDC’s coronavirus test kits began arriving at the 100 or so public labs across the country in small white boxes on Feb. 6, according to the CDC timeline in the review. Each cardboard container held four tiny vials of chemicals that, when used properly, were meant to confirm the presence of the virus.

The New York City Public Health Laboratory was in that first wave of labs receiving the kits, and its director, Jennifer Rakeman, said her technicians began trying to verify the test right away. Verification is a standard protocol; it involves following detailed instructions to ensure the tests work the same way in an outside lab as they do at the CDC labs in Atlanta.

John Minchillo/AP

The first three vials in the box were specific to the coronavirus, and the fourth was a control that let the labs know the specimen they were examining was a good one. Essentially, Rakeman said, it lets you know if the swab went all the way up a patient’s nose and wasn’t just “waved in the air.”

By Feb. 8, hours after her lab started verifying the test kits, Rakeman said she began receiving panicked emails from colleagues. Something, they said, was wrong: They had run the tests dozens of times but were getting inconclusive results from two of the reagents, or chemicals, in the vials.

Rakeman began calling other labs to see if they were experiencing the same problem, and they said they were. “It was very truly an ‘oh, crap’ moment,” Rakeman said. “These reagents aren’t working; everybody is waiting for us all over the city to have this test online. We think we have more cases than we’ve been able to detect and the test isn’t working.”

She said trying to battle COVID-19, which was just starting to rage through New York, without a test was like trying to build a house with a saw but no hammer. “And we need that hammer. We need that other tool, we need that test,” she said.

Contamination

When the complaints reached the CDC, leaders at the lab said they suspected the problem was contamination, according to Department of Health and Human Services officials who spoke to them at the time. Low-level contamination was to blame for a problem with a Middle East respiratory syndrome CDC test years ago. Microscopic residue could roil and ruin a sensitive test such as the one built to find the coronavirus.

Key CDC officials thought that might be the problem, too. “Contamination is one possible explanation, but there are others, and I can’t really comment on what is an ongoing investigation,” Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters in March.

Samuel Corum/Getty Images

The contamination theory gained momentum after Timothy Stenzel, director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health, visited the respiratory disease lab a few weeks later.

He returned to his superiors in Washington, D.C., saying he found sloppy lab protocols. Researchers entered and exited the coronavirus laboratories without changing their coats, he said. Testing ingredients were assembled in the same room where researchers had been working on positive coronavirus samples, he told them, according to three officials who were part of the discussion at the time. These are the sorts of things that can introduce microscopic contamination.

CDC and HHS officials disagree with Stenzel’s characterization of the lab. One former CDC official who was there when he arrived said the issues were small. “It was beakers on a counter that were empty and washed within 7 feet of a negative pressure hood. He called that dirty. Was that protocol? No. But it wasn’t a dirty lab.”

The FDA declined to make Stenzel available for this story.

While the CDC and HHS were trying to determine what was wrong with the kits, public labs were still waiting for something they could use. “We waited another month before we had testing available,” Rakeman told NPR.

”Absence or failure of document control”

Lindstrom, who led the respiratory disease lab, had invented diagnostic tests in the past. Before he went to the infectious diseases lab, he was running a different CDC lab, one that focused on influenza.

When he was there, he had helped create the diagnostic tests that were used to identify H1N1 in patients, and there were no issues with the test. The FDA quickly approved the kits and sent them to labs across the country. Within days, the same kits were dispatched around the world. The effort was considered a triumph for the CDC, and Lindstrom was viewed internally as the guy who made it happen.

The influenza lab, however, had an infrastructure and systematic way of responding to flu outbreaks, and because of that Lindstrom and his team just had to do the science, one official said. The infrastructure was already there to help. COVID-19 was different. When Lindstrom first built the test at the infectious disease lab, for instance, he didn’t have any human sample of the virus, so it had to be manufactured.

What’s more, officials say, Lindstrom built the coronavirus test the same way he would have built one for influenza. It was, after all, what he knew best.

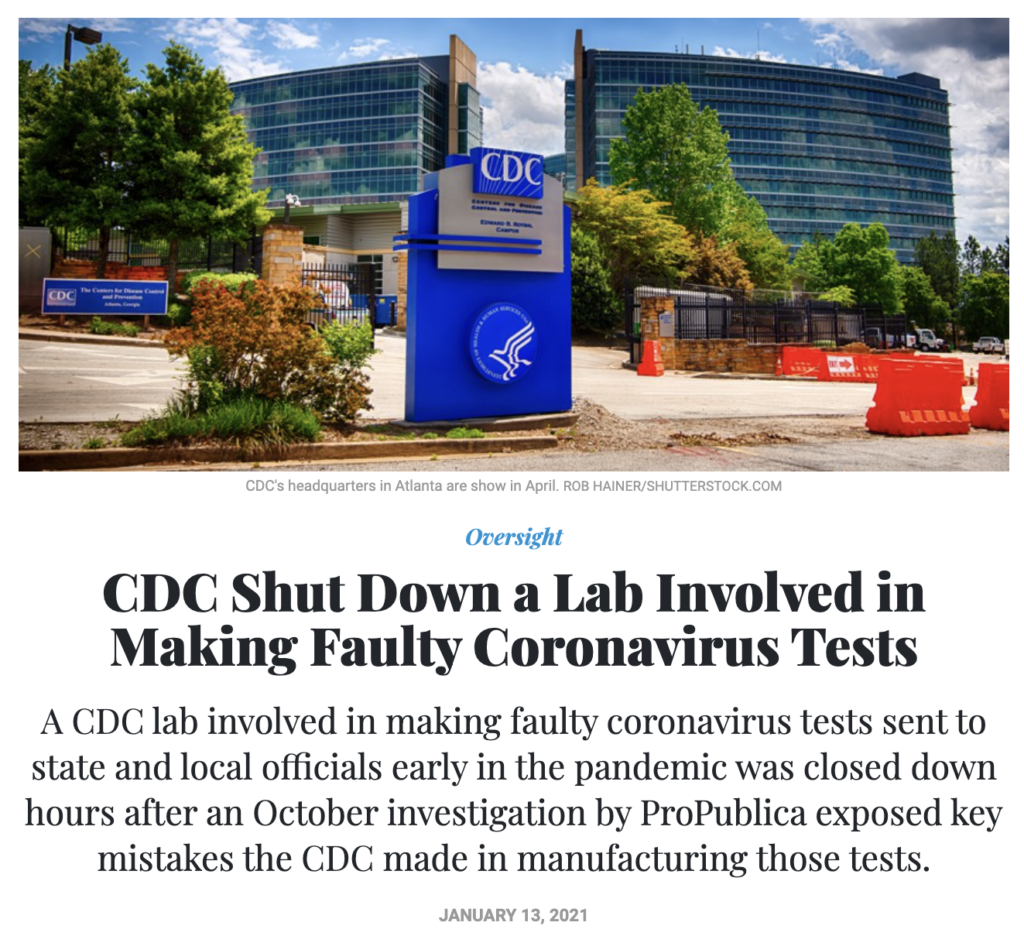

CDC Shut Down a Lab Involved in Making Faulty Coronavirus Tests – JAN 13, 2021

A CDC lab involved in making faulty coronavirus tests sent to state and local officials early in the pandemic was closed down hours after an October investigation by ProPublica exposed key mistakes the CDC made in manufacturing those tests.

With no public notice, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in October shut down a key lab involved in making faulty COVID-19 tests for state and local health authorities early in the pandemic. The move came less than six hours after ProPublica published [a] an investigation that detailed for the first time the chain of mistakes and disputes that unfolded inside CDC labs, which culminated in one of the biggest fumbles in the agency’s 74-year history.

[a] https://www.propublica.org/article/inside-the-fall-of-the-cdc

A CDC acting branch chief told the staff of the Respiratory Viruses Diagnostics Team lab on Oct. 15 that the closure would be for two to four weeks while the CDC investigated and the staff worked on corrective action plans, according to internal sources. But more than two months later, the lab still is not performing tests.

ProPublica’s investigation revealed that Stephen Lindstrom, a respected CDC veteran who led the lab and was in charge of the production of tests in the early days of the pandemic, made a fateful decision in January 2020 to use an internal CDC manufacturing process that was fast but risked contamination. Lindstrom then released tests to state and local public health labs the following month even though one of his staff’s quality checks showed that plain water tested positive for the virus, according to CDC lab records.

Complaints poured in from the state and local facilities shortly after the tests arrived. At that time, Lindstrom’s CDC lab was the only one in the country that could confirm whether a patient had COVID-19, and the scarcity of working tests at state and local public health labs had serious consequences in the early days of the pandemic.

The roots of that early public failure had remained largely a mystery, even to those within the CDC. ProPublica’s account of what transpired inside the lab was news even to some senior CDC officials. The story, based on interviews and exclusively obtained lab records, detailed the mounting pressures on the lab staff, the mystifying appearance of contamination at every turn and the three-week scramble to fix the tests.

Since then, work in the lab has been intermittent, with tests diverted for a time in March and a temporary closure in May. In October, the lab, which by then was no longer managed by Lindstrom, was faulted for making what higher-ups considered an error while handling materials for a new test designed to detect both the flu and the coronavirus, according to people familiar with the matter. It’s not clear whether that issue, the revelations in the ProPublica investigation or a combination of both led to the Oct.15 shutdown.

The CDC media team declined to answer questions about the reasons for the closure or the ongoing efforts to bring the lab back into compliance. Lindstrom referred a reporter to the media team, which did not make him available for an interview.

Debate has simmered within the CDC about whether the flawed tests were due to contamination, which can happen in the best of labs, or a faulty design. Two CDC labs were involved in making ingredients for the flawed tests in January and February last year, and a report by lawyers at the Department of Health and Human Services last June said Lindstrom’s lab was the likely source of contamination.

Lindstrom had created well-regarded tests for the flu, including the first test for H1N1 during that pandemic in 2009. Records show he was adamant that the COVID-19 test design was not flawed and that evidence showed the contamination happened at the other CDC facility that made testing components, not his own lab. In July he was reassigned to a new job with no official title and few responsibilities.

A different CDC scientist familiar with the Oct.15 lab closure said Lindstrom’s lab made mistakes. But the scientist, who asked not to be identified, said there was a sense among some CDC staff that Lindstrom and his team were being scapegoated and unfairly blamed for contamination that may have involved another CDC lab. The scientist believes that shutting down the lab on the day of the ProPublica story was to protect top CDC officials, including the task force in charge of labs during the COVID-19 response. “When something bad happens and it goes public, heads have to roll, and they pick people to take the fall,” the scientist said.

Additional Information:

Video: Prof. Sanjaya Senanayake said that we don’t have the gold standard testing for COVID-19

Dr. Astrid Stuckelberger: Injections Contain Graphene Oxide, Parasites, RFID, Metals, Nano Circuitry

If Covid tests aren’t accurate, how did Reliance make a kit that can show COVID-19 results in just 2 hours?

Source: Twitter, Rumble, npr, Government Executive