The recent implementation of new criminal codes in India has raised concerns among rights activists, and legal experts due to the significant changes they bring to the country’s criminal justice system.

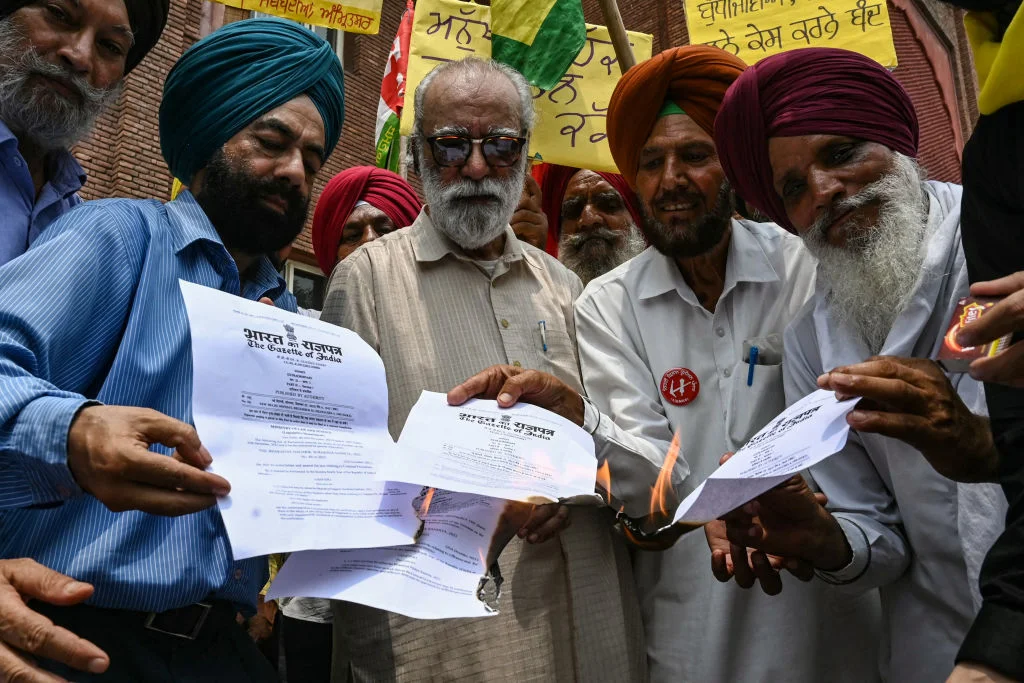

Opposition politicians have criticized the revised laws, claiming that they include provisions that are considered unconstitutional. This controversy has sparked debates and discussions among various stakeholders in the country.

The federal government has defended the changes by stating that the new laws aim to modernize the criminal justice system and address the evolving nature of crimes in contemporary society. The government’s stance on the issue has further fueled the ongoing debate surrounding the implementation of the new criminal codes.

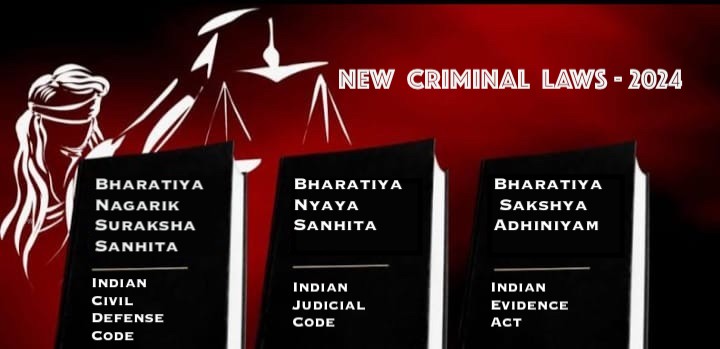

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS or Indian Judicial Code), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS or Indian Civil Defense Code), and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA or Indian Evidence Act) are the three new laws that were passed in the Lok Sabha (lower house of the parliament) in December last year.

The Bar Council of Delhi (BCI) has criticized the new provisions as “anti-people and more draconian than the previous laws,” and has called for a nationwide protest against the new laws.

According to Father Cedric Prakash, a human rights activist, the laws were passed when 146 opposition members of the parliament were suspended, and there were not enough discussions and deliberations in parliament.

Prakash, located in Gujarat, the home state of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, stated that the BCI, a statutory body of lawyers that regulates legal education and practice in the country, has already issued a call for a nationwide protest.

He also mentioned that the new laws are “repressive and would usher in a police state.”

“In accordance with the constitution of India, these new criminal laws must be immediately halted and prevented from being implemented,” he added.

Muhammad Arif, chairman of the Centre for Harmony and Peace, mentioned that the Modi government should have consulted with all the people involved, including opposition members of parliament and top legal experts, before getting rid of the old laws.

Muhammad Arif said the British-era laws did have all the provisions to address all types of crimes.

“Just changing the names of the laws won’t make things better,” he said. “It won’t improve law and order or make justice faster,” he told UCA News.

Arif, whose organization is located in the largest and most populous northern state of Uttar Pradesh in India, stated that Muslims were worried about the BJP government’s politics and policies, which have been perceived as anti-minority communities.

He also voiced his concerns about whether the new code would truly help ordinary citizens achieve justice or promote harmony among all individuals regardless of their caste, creed, and religion.

Arif mentioned that there has been a rise in religious polarization in India since the pro-Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) took power in 2014.

On July 1, federal Home Minister Amit Shah stated to the media that the new laws would revolutionize the criminal justice system into a completely indigenous one. He emphasized that these laws are in line with the Indian constitution’s principles.

He also asserted that once implemented, they will be recognized as the most contemporary set of laws.

Meanwhile, The Bar Council of Delhi (BCD) has voiced strong opposition to the newly introduced criminal laws, expressing serious concerns about their potential to disrupt the justice delivery system and undermine fundamental constitutional principles.

Aakar Patel, Chair of Board at Amnesty International India

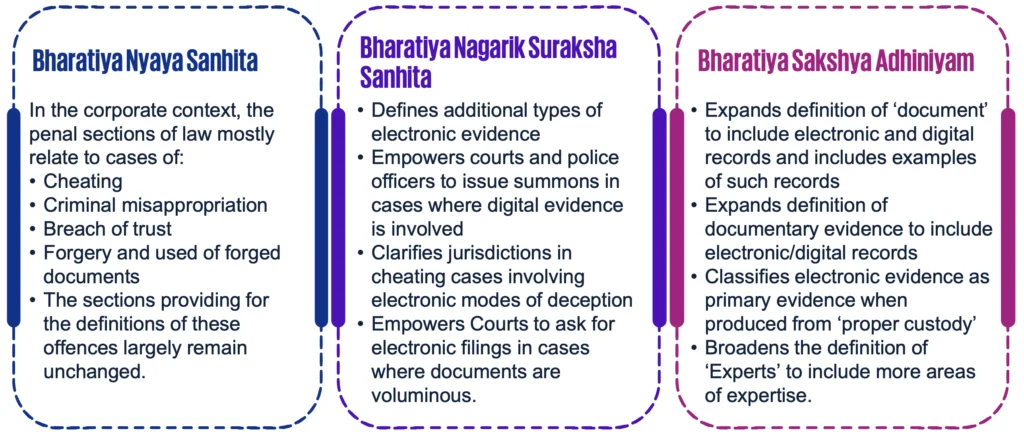

The new criminal laws in India, namely Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhinayam (BSA), have recently replaced three British-era laws, which has sparked concerns among human rights activists.

Aakar Patel, the chair of the board at Amnesty International India, has called for the immediate repeal of these repressive laws, citing that they pose a threat to fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, association, peaceful assembly, and fair trial.

Despite the Indian government’s claims that sedition laws have been abolished, it has been revealed that they have been reintroduced under the BNS, with a provision criminalizing acts that endanger the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India, similar to the old sedition law.

The BNS also imposes a minimum punishment of seven years, which is a significant increase from the previous laws, further raising concerns about the potential misuse of these provisions to suppress dissent and stifle freedom of speech.

The overhaul of criminal laws in India has raised alarms within the international community, with calls for the government to reconsider these amendments and ensure that they are in line with international human rights standards.

The BNSS, also known as the new Code of Criminal Procedure, now allows the police to request a 15-day custody of an accused at any point before the completion of 40-60 days of the permitted remand period, rather than just within the initial two weeks following an arrest. This ambiguity in the law creates an environment where torture and other forms of ill-treatment can thrive.

Similarly to the Indian Evidence Act, the BSA permits the acceptance of electronic records as evidence. However, due to the absence of a strong data protection law and the documented misuse of electronic evidence in cases like Bhima Koregaon and Newsclick, this new law opens up possibilities for exploitation and misuse.

As the laws currently stand, they could potentially be used as a justification to infringe upon the rights of individuals who speak out against those in power. It is imperative that these three new criminal laws in India are revoked promptly and aligned with international human rights standards to prevent further abuse and misuse in silencing peaceful dissent within the nation.

The Indian Ministry of Home Affairs presented the BNS, BNSS, and BSA bills on 11 August 2023 to replace the 1860 Indian Penal Code, 1973 Code of Criminal Procedure, and 1872 Indian Evidence Act in the Indian Parliament.

Background:

In 2020, a national committee was established by the Ministry of Home Affairs to review criminal laws in India, with the recommendations from this committee serving as the foundation for the bills introduced in 2023.

Despite claims of an extensive consultation process by the Indian government, the committee faced criticism for its lack of civil society and gender representation, and the final report was not made public.

Senior Congress leader P Chidambaramin tweeted:

The three criminal laws to replace the IPC, CrPC and Indian Evidence Act come into force today

90-99 per cent of the so-called new laws are a cut, copy and paste job. A task that could have been completed with a few amendments to the existing three laws has been turned into a wasteful exercise

The three criminal laws to replace the IPC, CrPC and Indian Evidence Act come into force today

90-99 per cent of the so-called new laws are a cut, copy and paste job. A task that could have been completed with a few amendments to the existing three laws has been turned into a wasteful exercise.The three criminal laws to replace the IPC, CrPC and Indian Evidence Act come into force today

— P. Chidambaram (@PChidambaram_IN) July 1, 2024

90-99 per cent of the so-called new laws are a cut, copy and paste job. A task that could have been completed with a few amendments to the existing three laws has been turned into a…

Source: UCA News, KNPG, Linkedin, Qvive